Norse warrior: “Is there mead in the afterlife?”

Thor: “Bwahahahahahahahaha!!!”

Norse warrior: “Ummmm…”

Thor: “Oh! Yes, indeed! My father’s hall is full of mead!”

Mead

Thor’s reaction gives you an indication of how the Germanic peoples (those we consider the German, Norse, and Anglo-Saxon) thought of mead, it’s even a bit of an understatement. Mead was the drink of the gods, of which the people happily shared with them, and would drink whole vats of while devouring roast oxen.

As far back as the 400s, after the Romans left Britain and the Anglo-Saxons took over, they made use of the many wild bees found on the island. In fact, pre-Roman Celtic Britons referred to their island home not only as the White Island, but the Isle of Honey. Even into the Norman Conquest, honey was nearly the only sweetener available and the lower classes of society’s only sweetener even into the 1600s. In Anglo-Saxon times, honey was also used to create mead. No matter what tavern you stopped in, town or village, they were almost assured to have mead on hand. Mead was used at royal banquets and by the monks. Extant writings even give the amount Aethelwold, Bishop of Winchester, allowed his monks at dinner: a sextarium, which is several pints. Not too shabby for a dinner!

There were three kinds of liquor made from honey by the Anglo-Saxons. Mead proper, the most common and drunk by the common people, was made by steeping the crushed refuse of combs after as much honey as could be was extracted. Morat was the honey and water mead with the addition of mulberry juice. The third was pigment, which was honey and water with spices added, and which we now call metheglin, and which was used by the top rung of society, being served at the royal table. If you’d like to try to make an authentic Anglo-Saxon mead, you can find directions here.

Much later, Sir Kenelm Digby (1603-1665) described mead as the Liquor of Life, although this was shortly before mead lost its pre-eminence. It was not without a fight, though, as in 1726, Dr. Joseph Warder stated that the meads of England were in no ways inferior to the wines of France or Spain. The Tudor Dynasty, though, with their insistence upon foreign wines, truly doomed the honey drink, even if the last of them enjoyed mead. Germany had a similar issue with a drop in mead production, due to the Reformation and the Thirty Years War (giving a time frame of the 1500s into the 1600s), which saw a drop of thirteen mead houses to only one.

Having thus been common and starting to fall out of repute as wine from the south started making its way into the country, it was still common in country houses up through the late 17th century, and was especially used for wedding feasts. There were exceptions, with Lancashire having a famous braggot into the late 1800s, with some towns having a “Braggot Sunday” celebration during Lent. Another exception is that beekeepers and some country women kept the practice of brewing mead going into modern times, with the caveat that the best mead was aged in wood. As well as the making of mead, these apiarists also kept the knowledge of the curative properties of honey in the collective wisdom, with it being used as a remedy for obesity, constipation, depression, indigestion, and irritability, and the bees, with their stings, were also used for arthritis and as an antiseptic. An ointment made of honey and turpentine was also used for bruises and sprains.

Queen Elizabeth herself had her own mead recipe, which has come down to us through the writings of her beekeeper Charles Butler. It is an easy recipe to find online, and is an interesting looking methaglin. It contains spices that should be easy to find, such as thyme, bay leaves, and rosemary, but then also includes a rarity of these days, sweet briar. It should also, like many meads, be left for six months or more before drinking, unless you don’t mind it being rougher than it need be.

Queen Bee as Queen Elizabeth (Kat Dreibelbis) Etsy shop

The Germans drank their mead out of silver tipped bull horns, something which Julius Caesar himself remarked upon. Obviously this was such an important aspect of their culture, that a thousand years later King Harold of Norway had such drinking vessels, adorned with gold and silver. A couple hundred years before in Anglo-Saxon England, King Witlaf of Mercia was another mead drinker who used decorated bovine horns. An ancient runic calendar from Scandinavia shows these horns being used as a symbol for Yule.

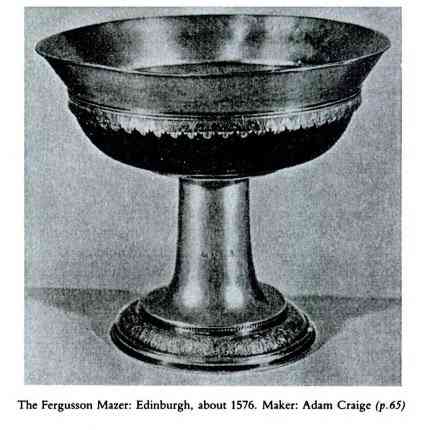

Eventually these horns went out of fashion and ornate silver cups and wooden bowls started being used in their place. These bowls were called mazers, from a Middle English word for maple, which was the favoured word to use when making the wooden version. Mazers came in many forms, including the mether cup, which was used solely for mead, unlike the mazer which was also sometimes used for wine or ale.

Mead crept into all aspects of the culture. The English word honeymoon is derived from the ancient European practice of giving a newly married couple enough mead to last a month, or moon’s cycle, as honey and mead were thought to enhance fertility.

In more linguistics of England, the word braggot, which is a Welsh word that did indicate beer possibly with honey, and now is a mead with beer grains, is instead said to have evolved from the Norse god Bragga. Obviously, linguistics shows us that it is of Welsh origin, but it is greatly fascinating to see what other origins are given to words over time, regardless of historical accuracy.

In further linguistics (isn’t this fun?), the English word supper comes from the Anglo-Saxon supan, meaning “to drink,” as opposed to dinner, which is from dynan for “to feed,” giving every indication that our later evening meal should definitely consist of some ale, mead, or wine. In fact, evening comes from aefen, which is “drinking time.” Another term still in rural use is skep, for a bee home, coming from skeppa for “basket.”

In literature, the Wassail bowl is mentioned in Shakespeare’s Midsummer Night’s Dream, in the line “sometimes lurk I in a gossip’s bowl.” It is explicitly given in his Hamlet, with the actual word wassail being used. Chaucer shows the sweetness in Miller’s Tale with “her mouth was sweet as braggot or metheglin.”

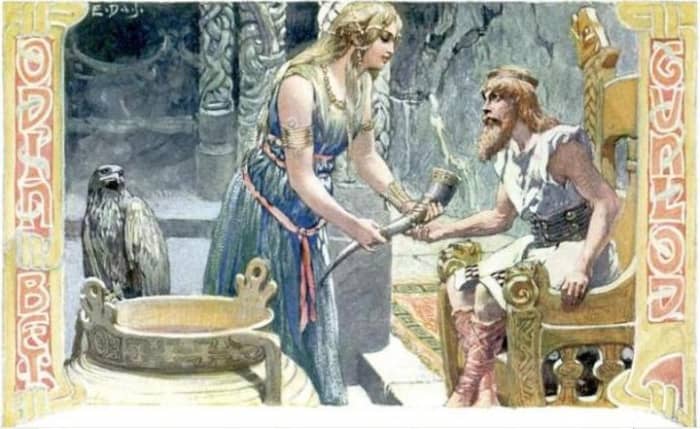

Perhaps the most well-known tale of mead is that of Odin’s mead of poetry. A tale too long for here, and told superbly by others (although perhaps I shall give it my own spin soon, as I did with the spooky tale of Nera, it is nonetheless more than a simple worth of mentioning. Odin’s mead is the Mead of Inspiration. Without it, we would have no poetry. Poets of yore were called “bearers of the mead of Odin,” because of this influence. Such an influence does have its negative side, though, with bad poetry being the cause of drinking Odin’s mead created urine. The famed American writer Walt Whitman even insisted that poets speak not just with intellect, but with intellect inebriated by nectar.

Odin is offered the Mead of Poetry by Gunnlod. Public Domain

Honey

And where would we be without the magical pot of bee spit that gives us mead, honey! Although not as deep in lore as the Celts, there is still evidence of a great love of the bee and honey.

In Germany, if you find a swarm of bees on a branch, if you use this branch to lead cattle to market, they will fetch a higher than usual price. A bee alighting on someone’s hand signifies money and alighting on the head signifies life success.

Even after the Christianization of the northern countries, The Finns thought the sky was God’s storehouse, where was kept the heavenly honey that healed all wounds.

The great Anglo-Saxon king, and nearly the first of England, Alfred required all bee keepers announce swarms by the ringing of bells, so that they would be followed and captured. At the same time, the Catholic Church required wax candles, and so bees were a necessity for religious life.

Wassailing

Another aspect of mead was its use in social situations, where in it was drank while boasts were made and pacts were sealed. A part of this is the toast, an honouring with drink, which was a very significant part of feasts for both the Norse and the Anglo-Saxons. From the Anglo-Saxon saga Beowulf, we learn of the appropriate salutations for drinking with mead. These are “wacht heil,” meaning “be whole,” when giving the mead and “drinc heil,” meaning “drink, hail!” The first is the only typically still used and has become our now beloved “wassail!”

Wassailing Public Domain

Wassailing eventually became the act of drinking to the health of trees, more than likely a nod to pagan times and giving honour to nature. Revellers would walk around the tree and wassailed it three times with:

Here’s to thee, old apple-tree

Whence thou may’st bud, and may’st blow!

And whence thou may’st bear apples enow!

Hats full! Caps full!

Bushel – bushel – sacks full!

And my pockets full too! Huzza!

And so as we finish this article, I say unto you, the reader, “wassail!” I toast and honour you, and may we meet under the long roof of Valhalla where we shall drink from the rivers of mead and dine from never ending roasted boar.

NOTE: You may notice some of the words are spelled differently throughout. These are not errors, but rather I have used all of the different spellings that occur in my research reading. Such wonderful fun!

https://owlcation.com/social-sciences/The-Lore-and-History-of-Mead-in-Germanic-Cultures

.jpg)